ENGLISH TEXT

THE RACE OF THE SEMICONDUCTORS

A critical look at the microchip trade war and its implications for humanity and the planet. The chip is the new axis of global power, a capacitor of knowledge, capital, and military coercion that redefines planetary conditions. Controlling its supply chain means imposing the rules of the game in almost all areas of life: electric mobility, digitalized health systems, finance, smart weaponry, and surveillance networks that condition our daily lives.

By 2025, global chip sales are reaching trillions of dollars, driven by the voraciousness of generative artificial intelligence and the expansion of data centers. But behind this growth, we see increasingly aggressive geopolitics: the United States imposes export controls to strangle China’s access to advanced technologies, while Taiwan (which concentrates nearly 75% of the world’s semiconductor manufacturing capacity) becomes a strategic bottleneck in the South China Sea, a scenario where economy, security, and sovereignty collide directly.

The dispute between the United States and China has turned the market into a war front, where sanctions and strategic pacts place so-called “technological security” above any notion of global equity. But behind that rhetoric lies an insatiable appetite: lithium, cobalt, rare earths, tantalum, water, excessive energy, and toxic chemicals ripped from peripheral territories.

The ecological and social debt is growing ever larger, while global power is built upon devastation.

This industry replicates colonial patterns of plunder, only now with drones and investment contracts. The Spanish sword coveted Andean gold, the British Empire Amazonian rubber, and the oil of the twentieth century unleashed proxy wars; today, the fever for minerals like cobalt in the Congo, and lithium from the Lithium Triangle in Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina, generates analogous conflicts.

The Democratic Republic of Congo supplies 70% of the world’s cobalt; mining expansion has caused the forced eviction of thousands of people, child labor in lethal conditions (with at least 35,000 children exposed to toxic pollutants), abuses, and river pollution affecting the health of entire communities. In Chile and Bolivia, lithium extraction depletes aquifers, salinizing soils and displacing indigenous peoples like the Atacameños, whose cultural sovereignty is affected in the name of the “energy transition.”

The patterns are identical: transnational corporations concentrate capital to extract; states that facilitate with subsidies and repression; local communities absorb externalities like water poisoning and violent incidents in mines, from suppressed protests to the murders of activists.

The map of microchips is an atlas of exploitation.

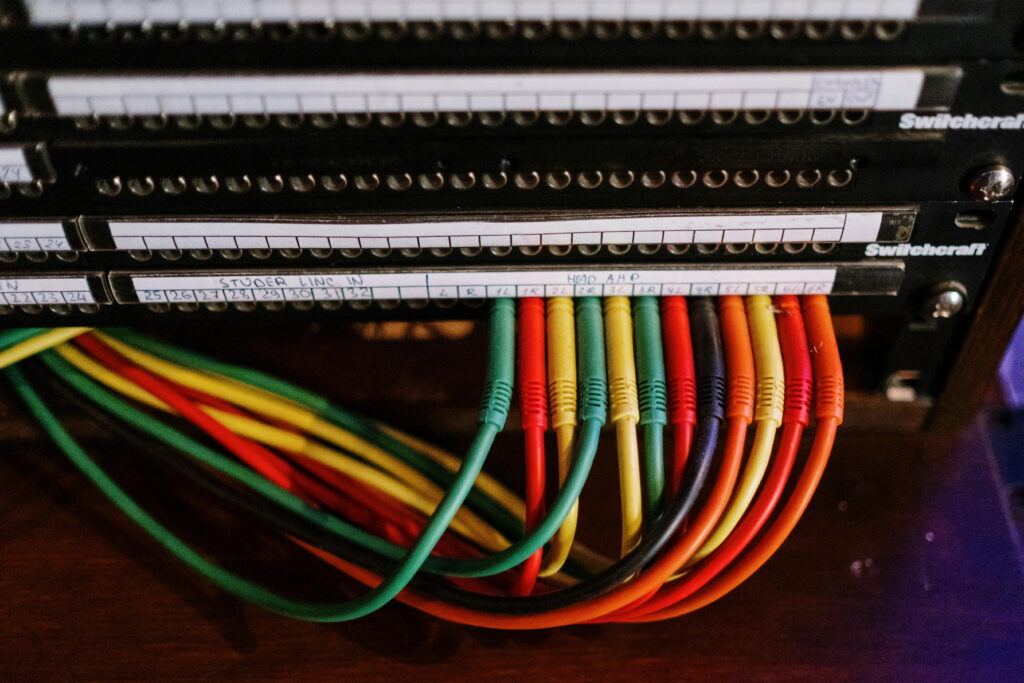

Mines in Africa and Latin America connected to smelters in China, factories in Taiwan, and laboratories in California, weaving a network where wealth flows upward and devastation is dispersed downward.

Semiconductor manufacturing consumes energy equivalent to that of entire nations, with CO2 emissions projected at 277 million metric tons by 2030, growing at 8.3% annually. It requires up to 10 million gallons of ultrapure water per factory per day, thus exacerbating droughts. It also releases fluorinated gases and acids that pollute air and soil in the long term, with toxic legacies impacting the health of workers and residents, such as in US complexes where high cancer rates are reported.

The industry sells smaller chips, faster processing, but hides exhausted aquifers in Arizona, toxic spills in Malaysia, and e-waste exported to African landfills where children dismantle circuits for pennies, inhaling lead and mercury.

Profits privatized on corporate balance sheets, costs socialized on sick lungs and collapsed ecosystems.

Politics and economics blur in this frantic race, where states allocate subsidies to bring factories back. They do not do so out of ecological awareness, but out of fear of so-called “resilience” against China. Geopolitical blocks impose restrictions on the export of Dutch machinery, consolidate exclusive pacts like the Chip 4 (US, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan), turning trade into a scenario of permanent confrontation.

The chip race has created a scenario where environmental and labor standards are relegated in the face of so-called “strategic urgency.” In the Democratic Republic of Congo, corrupt officials turn a blind eye to systematic abuses to attract investment. In Chile, bilateral treaties shield extraction above the rights of indigenous peoples. What should be a common problem (climate and social stability) becomes a sum of fragmented interests, where each nation fights its own battle.

Thus, a kind of technological armamentism is perpetuated which, in the name of progress, ignores the ecological and social limits on which our survival depends.

We consume devices under the promise of “unlimited connectivity” without stopping to think about what is left behind: ravaged soils in Mongolia from rare earth extraction or broken lives in Congolese mines. The marketing from Apple and Samsung makes us believe that an OLED screen or AI software represents progress, while hiding miners exposed to radiation in tantalum mines and operations that fund armed militias.

Technology will not replace natural ecosystems. A forest is a symphony of biodiversity, ecosystem services, and indigenous knowledge that no silicon simulation can replicate. This anthropocentric vision not only accelerates the sixth extinction, it legitimizes the abandonment of care, positioning the machine as a post-apocalyptic savior.

The dominant trajectory of more extraction, fortified factories, and militarized subsidies leads to collapse. Let us demand radical transparency in supply chains, with blockchain traceability for minerals; extended producer responsibility, where companies like Intel fund remediation at mining sites; and global regulations that eradicate planned obsolescence, promoting modularity and repairability, reducing e-waste by 50% through circular designs.

Public policies must incentivize low-material technologies, such as chips based on recycled materials or urban mining of metals from e-waste, extracting gold and copper from urban landfills instead of virgin mines. Extractive nations like Congo and Bolivia must transition from raw exporters to processors with added value, under ILO labor standards and UN environmental standards, with binding community participation in impact assessments.

The knot of power is not undone with corporate philanthropy; it requires democratization. Counterweights like public control over strategic decisions, independent audits, and direct compensation to those affected. Without this, critical minerals become geopolitical currency, subjugating populations to remote whims.

The metaphor of the forest in a circuit is not poetic; it is a dystopian prophecy.

Reorienting this trajectory is not a benevolent option; it is a revolutionary imperative. The governance of digital resources must be transparent, equitable, and publicly scrutinized. We must not sacrifice the planet for a chimera.

NO ONE IS SAVED ALONE

An analysis of how self-help manipulates, fragments, and blames us, while simultaneously offering individual solutions wrapped in motivational phrases.

The so-called “personal growth” is nothing more than an opiate that convinces us our failure is always our own fault. A machinery that transforms social malaise into private business and frustration into motivational merchandise. A factory of individuals busy adjusting themselves while the world burns around them.

Byung-Chul Han called this the “achievement society”: cheerful self-exploitation, mandatory positivity, exhaustion wrapped in motivational phrases. “Everything depends on you” while the ground shakes with stagnant wages, rising rents, long workdays, and high credit. It then seems that every stumble is an “attitude” problem, and the economic order remains safe from all criticism.

We see everywhere videos explaining how to achieve “financial success in 30 days,” while millions of people work in conditions that will never allow that promise. Or the proliferation of “happiness apps” that send you notifications reminding you to smile, as if joy were a switch. Or the fitness influencers who, amid a global healthcare access crisis, proclaim that everything depends on your discipline to not eat bread.

A person overwhelmed by debt is persuaded to buy a “millionaire mindset” course. A woman overloaded by the double burden of paid and domestic work finds gurus on Instagram telling her that her problem is “not vibrating high enough.”

Precarity is individualized and medicalized, while the structure that generates it is rendered invisible.

In productivity reels, in “abundance mindset” courses, in podcasts that turn inequality into a personal challenge. The circuit is completed by media outlets, platforms, and publishers that align the emotional offer with the needs of the market.

The major publishing houses that fill shelves with self-help books belong to conglomerates with global interests. Companies that select and scale what sells, and what sells most today is the promise of self-improvement.

Books like Secrets of the Millionaire Mind by T. Harv Eker, Think and Grow Rich by Napoleon Hill, or The 5 AM Club by Robin Sharma have become embedded in the cultural imagination. So much so that phrases like “if you can dream it, you can achieve it” or “you are the result of your habits” are repeated like mantras.

If Christianity implanted original sin as the indelible mark of humanity, spiritualized self-help has created its modern equivalent: the guilt of not always being grateful, positive, and balanced. In the catalog of packaged spirituality, we find books selling “the magic of angels,” prayers for prosperity, crystals that “align your energy” while the bank charges you credit card interest. A supermarket spirituality that mixes scraps of New Age religiosity, prosperity gospel, and emotional marketing.

In its origins, philosophy dealt with God and the divine; later, with politics and the organization of the polis. Today, after the wear and tear and loss of authority of religious and political institutions, much of popularized philosophy has moved into the terrain of self-help or, better yet, self-failure.

What was once an exercise of radical thought, confrontation with the absolute, or reflection on the social order, is now motivation capsules circulating on social networks like fortune cookies with intellectual pretensions.

The Stoicism of Marcus Aurelius or Epictetus, which conceived serenity as a way to live with dignity in the face of the inevitable, has been degraded to a manual of productivity and obedience. What was a philosophy of resistance has become resilience elevated to a supreme virtue, functional to a system that prefers us resigned rather than critical.

The content that feeds this feeling of permanent lack is produced and distributed on platforms where advertising rules. The business consists of keeping us watching and buying. The attention economy needs you to always feel just inches away from “your optimized self.”

We are trained to read any criticism as “toxicity,” any mention of injustices as “drama.” We stop listening to the friend who points out abuse, a complaint, or any distress.

‘Divide and rule’. We are separated from others under the argument that their “negativity” is contaminating.

The market thanks fewer uncomfortable bonds, more consumption of solutions in the name of personal growth.

On the surface, self-help stems from modern psychology, but scientific psychology studies human behavior in its complexity, while self-help reduces it to consumption strategies.

This industry recycles scientific terms (neuroplasticity, quantum physics) out of context to confer prestige. The book and film The Secret popularized a doctrine that confuses metaphysics with quantum mechanics; skeptical magazines and communicators have been debunking it for years.

Even environmental language was redirected towards intimate guilt. The “carbon footprint calculation” popularized by BP campaigns in the 2000s shifted the focus from the industrial emitter to the consumer: if you don’t recycle perfectly, if you don’t change your lightbulb, if you don’t pay your “offset,” you are part of the problem.

BetterHelp and other platforms privatize access to mental health in a subscription format; large companies buy “resilience packages” for exhausted workers.

Apps like Headspace or Calm sell their corporate version to thousands of companies and offer usage dashboards to HR, allowing the extraction of intimacy metrics for labor optimization purposes. This commodification of mental health raises dilemmas of privacy and displacement of responsibilities.

LinkedIn turns job precarity into a problem of personal branding and “reskilling”; the demand for a growth mindset becomes a company dogma. Viral posts celebrate the resilience of those who work 16 hours. Instead of questioning, the user submits to an infinite cycle of networking and reinvention.

The ecosystem that calls uncertainty “flexibility” turns your career path into a flow of quantifiable signals (endorsements, badges, “skills”) that push you into an infinite recycling of courses, mentorships, and micro-certifications. Each new diploma promises to close “the gap” that the market itself reopens a month later.

The figure of the “business shark” is necessary, not because we can all be sharks, but because the majority ends up accepting being bait with a smile, convinced that “it’s all a matter of attitude.”

The idols of entrepreneurship who “started from the bottom” are often used as examples. But that “bottom” is not the same for everyone. Starting from a garage in Silicon Valley with access to capital, contacts, and a good education is not the same as growing up in a marginalized neighborhood where daily survival is already a challenge.

The starting line is not the same.

Personal growth is not harmless.

Socially, it normalizes inequality: the poor are poor because they want to be.

Environmentally, it sells an infinite growth incompatible with a finite planet.

Mentally, it fuels epidemics of anxiety and depression, because every failure is interpreted as an internal flaw.

Culturally, it exports an individualistic model that colonizes collectivist societies.

With all of the above, I do not intend to deny the value of therapy, spirituality, or personal effort. It is about understanding what happens when personal relief is used to cover up social wounds. When a practice that could strengthen us communally reaches us as a subscription and comes with the order not to “get contaminated” by the pain of others.

You are offered balms that return you to the wheel: they calm you just enough to keep pedaling, not to change the bicycle.

While we spend hours “building our best version,” we forget that what makes us sickest is not a lack of motivation, but an excess of exploitation; not the absence of individual purpose, but communal disconnection; not that we lack positive affirmations, but that we have a system that turns all our vulnerability into merchandise.

If personal growth wants to stop being a placebo, it must look at structures as well as habits. It must admit that no one saves themselves alone. And that, finally, it must make power uncomfortable, that power which offers us mirrors so we worship our reflection while the world slips away from us.

Science Fiction as a Mirror of Reality Chronicle of a Future in Motion

Science fiction was never an oracle, but an art of projection. When Jules Verne imagined the Nautilus in 1870, he did not possess visionary powers; he simply extended the naval advances of his time to the point of verisimilitude. George Orwell, in 1984, did not describe Facebook or Google, but the totalitarian control machinery of his era. But he did it with such force that, decades later, politicians and technologists found there a vocabulary to justify cameras on streets and algorithms in networks.

What begins as literature ends as a roadmap. Engineers trained on reading Gibson invent cyberspaces; entrepreneurs raised on the fever of Stephenson found metaverses; military officials obsessed with Clarke design satellites that spy from orbit. The cycle repeats like a mill wheel: first imagination, then technique, later political normalization, and finally, social custom.

The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

What in sociology is known as the “self-fulfilling prophecy” is, in the cultural realm, a mechanism of infinite reproduction. A novel poses a scenario; a young reader internalizes it; years later, having become an engineer or a minister, they work to realize it.

Neuromancer (1984) invented cyberspace; today we live in it. Snow Crash (1992) conceived the metaverse; Silicon Valley invests billions in its construction. Minority Report (2002) showed personalized advertising and predictive policing; today Google and Palantir fulfill the mandate. And Contagion (2011) detailed the sequence of a pandemic: quarantines, viral rumors, round-the-clock vaccines. In 2020, millions watched it as if it were the news.

We are not talking about prophets. We are talking about writers capable of taking trends to the extreme. But in doing so, they inoculated these visions into the bloodstream of culture.

The Distorted Mirror of the Human

Aldous Huxley in Brave New World did not invent fictional drugs or genetic castes on a whim: he took them from the eugenics of his time and the Fordism that mechanized daily life. His society, anesthetized by soma and enslaved by consumption, now looks all too much like a world of mass-prescribed antidepressants and screens that administer pleasure like a drug.

Hugo Gernsback’s pulp vignettes showed video calls in the 1920s; today Zoom has turned us into floating faces on screens. And in The Matrix, the Wachowskis asked if we might be living inside a simulation, and it only took artificial intelligences starting to fabricate fake images and voices for that suspicion to become a habit.

How much of what we experience was initially conceived on the pages of a novel?

But this is not an exclusively Western phenomenon. Chinese science fiction, led by Liu Cixin, now dictates the conversation on artificial intelligence and space exploration. In Nigeria, Nnedi Okorafor blends African tradition with futurism to rewrite the destiny of her continent. In Latin America, writers like Angélica Gorodischer or Jorge Luis Borges, who in his “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” imagined a fictional world that devours the real one.

Hollywood, publishing houses, big tech: they all fuel the fictions that they later normalize. Entertainment is the opium of the future, the drug that prepares the masses to accept as natural that which would have previously seemed unacceptable.

Every time someone opens a book, watches a movie, or immerses themselves in a series, they are rehearsing a destiny. And destinies, when rehearsed enough, become realities.

HEAT_BUSINESS_

Ancient builders learned to read the wind, the shade, the radiation, and the water. From that reading emerged thick limestone walls that buffered the Mediterranean summer, Andalusian courtyards that cooled through water and shade, Arabic techniques that used evaporation to cool the air, Nordic dwellings oriented to capture light during prolonged winters. Those works did not separate house and territory: they assumed that to inhabit is to adjust body, matter, and climate into a continuity.

Glass, steel, and concrete are now deployed from Miami to Oslo as if the sun, wind, humidity, soil, and local culture were disposable variables. Standardization fits with global supply chains, assembly manuals, insurance that rewards the already proven, and investment portfolios that need comparable assets. The city ceases to be thought of for those who live in it and becomes designed for those who capitalize on it.

Cement is responsible for around 8% of global CO₂ emissions; steel and glass form an industrial tripod with few players capable of controlling extraction, energy, transport, and credit. Civil works become a machine that transforms limestone, coke, iron ore, and gas into predictable financial flows. The real cost (embodied energy, urban heat, associated illnesses, drainage works, flood losses) is deferred or socialized. What is privatized is the profit; what is collectivized is the damage.

Part of the current building stock is designed to guarantee captive energy demand.

Poorly oriented glass facades, sealed surfaces, hard plazas, and dark roofs raise the temperature of the environment and force cooling. Air conditioners, by expelling heat into the street, exacerbate the problem they claim to solve. A dependency is, literally, built. When the thermometer rises, the power company wins. When the sewer collapses, the emergency-contracted public works company wins. When health deteriorates due to thermal stress, the healthcare system pays, not the developer’s balance sheet.

Asphalt and concrete absorb radiation and slowly release it at night; the loss of vegetation eliminates evapotranspiration (nature’s free air conditioning); the street-canyon geometry traps hot air; traffic and machinery add anthropogenic heat. The consequences are heat islands that raise the temperature several degrees above the surrounding rural area, with deadly peaks during heatwaves. Deaths from hyperthermia, fainting, loss of labor productivity, and failures in critical networks are not “collateral damage”: they are predictable effects of formal decisions.

The greater the impermeable surface, the greater the runoff and the higher the peak flow in less time.

Water that once infiltrated living soils now bounces off concrete slabs and runs into a drainage network designed for medium storms of another era. Wetlands are filled in, streams are channeled, construction occurs on floodplains, and then the rain is blamed. Corrective works (storm tanks, oversized collectors, new dikes) come later, more expensive than having designed from the beginning with porosity, retention, and absorbent soil.

It is worth remembering that we already knew how to do it better. Persian qanats moved water underground without overheating the surface; Roman roads incorporated drainage into their very section; Teotihuacán integrated canals and vegetation to stabilize temperature and humidity.

Sustainability is not a recent discovery: it is a neglected knowledge because it disrupts the profitability of industrial repetition.

Bare, shadeless plazas discourage staying; people migrate to the air-conditioned interiors of shopping malls, where all interaction is reorganized around consumption. Offices with glass skins separate the interior from the real climate and normalize artificial air as the only response. Large roads and parking lots distribute daily time and energy towards the car.

Public life becomes a sequence of controlled, monitorable, and monetizable interiors.

Those with means buy air conditioning, reserve places in high zones, and pay for insurance; those without, face the heatwave with a fan and a bucket, and watch as the water carries away their house. The built form perpetuates inequalities and manufactures new ones.

And although research offers other alternatives—such as materials with very high thermal performance, bio-based composites with low embodied energy, nature-inspired systems that manage water and heat with physical elegance—they do not reach common housing because the decision circuit (regulations, insurance, banks, tenders, awards) rewards the known. We are taught to design to impress the render, not to lower the street temperature by five degrees at three in the afternoon. Projects are evaluated by initial cost, not by lifecycle cost.

“Powerful image” is valued, not continuous shade nor soil that drinks.

A shift is possible and does not require miracles. It requires will. Where shade is prioritized, thermal stress decreases. Where soil becomes soil again, the peak flow flattens. Where thermal mass is insulated to the exterior and cross-ventilated, the need for machines declines. Where water is returned to its course, the city stops fighting the watershed. But these decisions alter value chains; that is why they meet resistance: fewer square meters of glass mean fewer sales for certain suppliers; more living green implies fewer paving contracts; designing to last reduces capital turnover.

As long as the business depends on buildings that heat up and soils that do not absorb, heat and water will continue to punish. Contemporary architecture has amply demonstrated that it can produce dazzling buildings. The urgent thing is for it to once again produce shade, coolness, porosity, and memory. To change the metric of success: fewer kilowatt-hours, fewer degrees at street level, fewer millimeters of water reaching the collector, fewer hospital beds occupied by heatstroke.

When a city decides to plant trees in series, open up the soil, replace opaque skins with solar protections, limit height where the wind is choked, and renovate with breathing materials, it is not “going back to the past”: it is affirming that life is worth more. Inhabiting, ultimately, is nothing other than that: putting technique at the service of the common body. And in that order, every permit, every tender specification, every facade, and every tree is a political pronouncement.

If we continue to build heat and flood, it will not be for lack of alternatives, but for an excess of interests. If we decide otherwise, the city will show it in full light… and in good shade.

The ridiculousness of our wars.

Nature needs to pronounce no words to have its sentence engraved with fire, mud, or water. In the collapse of a Siberian slope, in the roar of an ocean threatening to swallow entire archipelagos, or in the overflowing rivers that sweep away walls, maps, and homelands, there is a message that should leave us speechless: none of this belongs to us.

Humanity has drawn lines on the earth with the obsession of a child scribbling on paper, believing it has created a world. It has declared independences as if a piece of the planet could emancipate itself from the planet itself. It has built walls, flags, anthems, and treaties upon ground that trembles, cracks, sinks, floods, and burns. And yet, we insist on believing we own what was never given to us to possess.

The recent geological, climatic, and hydrological crises are tremors from the living world clamoring for our attention. The atmosphere no longer distinguishes between North and South. Because nature knows no geopolitics and needs no ambassadors to speak to the world.

We say there are wars over territories. But we do not fight for the land; we fight for the narrative of the land. The true land is not in dispute: it is sovereign in its own right. It decides when to germinate and when to engulf. It owns its rhythms and is alien to our delusions of ownership. It lends us a place, and when it deems necessary, it takes it back.

But let us make an effort to go beyond the mountains, beyond the clouds, beyond the artificial satellites. Let us observe from on high, from where there is neither East nor West, neither civilization nor barbarism, neither rich North nor impoverished South. From there, from that point suspended in the darkness, that “pale blue dot” of which Carl Sagan spoke, all imperial arrogance dissolves into cosmic dust. Every fluttering flag is but a piece of cloth shaken by a wind that recognizes no kingdoms.

What are we, then, but momentary travelers on a borrowed rock, wrapped in a thin atmosphere that we have now begun to poison?

There is no nation before an earthquake. No army can stop the ocean. No constitution can save from ecological collapse. The Earth does not fragment according to our assemblies. It recomposes itself according to its cycles.

And when it awakens, it does not ask for our deeds, our coordinates, or our exploitation rights. It simply acts. Because true sovereignty resides in that which lives without asking permission.

Perhaps the time has come to retrace the history of conquests and begin an era of humility. For whoever understands that there is no “outside” of the planet will need no more wars. Only then, when we recognize ourselves as part of what we have wanted to possess, will there be a chance for continuity.

Until then, let us continue to contemplate, from the distance of reason, the small celestial dot. So beautiful. So fragile. So ignored.

The Public Opinion Factory

Bot farms are groups of fake accounts managed by computer programs that pretend to be real people.

Thousands of accounts posting nearly identical messages become a speaking swarm, and in this saturation, the human element is lost amidst so much noise.

And if you ask what portion of internet traffic is artificial, the answer is at least half. Nearly 50% of web traffic is generated by bots, of which 20% are malicious.

It is estimated that up to 15% of Twitter/X accounts are bots, representing some 48 million fake or automated accounts.

These farms use programs that post automatically, lists of words to vary the text, and tricks to hide their non-human nature. Now, with advances in artificial intelligence, they generate messages that sound like normal conversations, on a large scale. This allows them to create fake trends, fill hashtags with junk to bury criticism, or harass anyone who bothers them—all to distort what seems important in a community.

On networks where popularity is measured by likes or shares, controlling those numbers is like hacking collective attention.

The philosopher Byung-Chul Han, who has analyzed the “attention economy,” explains that what matters is no longer truth, but visibility.

A case documented by the University of Oxford in 2019 showed that at least 70 countries had implemented some type of digital manipulation operation using bot armies. In Mexico, for example, it was discovered that electoral campaigns were artificially inflated using automated programs that replicated arguments at such speed that Twitter’s algorithm placed them in trends.

In Russia, investigations into the Internet Research Agency showed that a small group of operators, with the help of thousands of fake accounts, managed to influence global political discussions, from the war in Ukraine to presidential elections in the United States.

A large human army is not necessary; a core of programmers and servers managing hundreds of thousands of fake profiles is enough to alter the global public agenda.

No matter the country; the method is copied: mix social tricks with automation to buy cheap attention. Dozens of governments and parties pay for digital “teams” to steer online conversations, using public or campaign money to hire external help and amplify coordinated messages.

But there is data. A lot of it.

An experiment by the University of Amsterdam brought together 500 bots with varied personalities. They didn’t even need complex recommendation algorithms; in a minimally social environment, the bots quickly formed echo chambers, polarized positions, and cemented a few artificial “influencers.”

Without mediation, the network’s structure was enough to foster division.

A second data point: around the race to elect the Speaker of Texas in 2025, a firm detected that many negative comments did not come from outraged citizens, but from bots created to simulate anger. Although the politician in question won, the episode showed how easy it is to manufacture opposition out of thin air.

It is estimated that bots generate content at an overwhelming speed, being up to 66 times more active than an average user, and in intense discussions they represent up to a third of the content, despite being a minority in number.

Networks show the most viewed or commented content first, and people use that to decide what to read. If a program generates thousands of fake interactions at low cost, it tricks that guide, making something seem massive when it is not. This leads to a social effect where, if you believe your idea is in the minority due to the fake noise, you prefer to stay silent. Cases in countries with strict control show that when these fake networks are shut down, more people feel encouraged to speak, because the perception of popularity influences whether you dare to or not.

When real humans perceive that their opinions are in the minority based on artificial signals, they fall silent because the digital environment convinces them their opinions lack value.

If a detector finds bots by their repetitive patterns, they switch to random variations, use AI-generated text that seems unique, or even pay people for the difficult parts. Tools for hunting bots admit they can no longer easily distinguish fake from real, especially with mixtures of human and AI. In recent years, the big change is that they now hold long conversations, adjust their tone to each person, and create tailored arguments.

Every defensive advance generates an offensive evolution. The attackers are always one step ahead because they are convincing enough during the critical time to influence an irreversible decision.

The farms are fueled by the platforms and their rules. By prioritizing what generates reactions, they reward conflict over useful information, creating closed groups that exaggerate extremes and give power to a few.

If the structure already leans toward chaos, an operator only needs to add fuel.

When interactions become a show of false numbers, it isolates people in bubbles where bias grows, prioritizing likes over authentic connections. The pressure to be visible leads to selling oneself out, handing over data that is later used to manipulate minds.

These automated propaganda tactics spread across the world, turning communication into a weapon of unequal power. Online subgroups use them to radicalize, pushing extreme ideas with viral images and bots that set topics. In social movements, they help organize, but also spread lies that confuse and weaken. Falsehood is armed by a team, with various actors creating networks that seem natural, catching unsuspecting users off guard.

Bot farms win when we confuse quantity with reason and attention with truth.

The most accurate metaphor is perhaps that of a virus: bot farms are informational pathogens that infect the social body. They don’t destroy directly, but rather disorganize the defenses of public opinion. It can no longer differentiate between the real and the artificial, thus generating apathy, polarization, and widespread distrust in institutions.

THE INVISIBLE HAND OF LOBBYISTS

An analysis whose publication led to the suspension of my accounts on Meta’s platforms, demonstrating the extent of corporate influence over digital free speech. Every day, we make decisions based on the information around us: what we eat, how we use technology, which medications we trust, or which policies we support. We believe these choices are free, informed by objective facts, and guided by the common good. But behind the laws, headlines, and products we consume, there’s a powerful force shaping what we know and believe: lobbyists. These professionals, backed by major corporations, work tirelessly to align public policy, science, and social perception with their clients’ interests.

In English, “lobby” means “vestibule” or “waiting room.” Historically, it referred to the halls or common areas of important buildings, such as parliaments or legislative chambers, where people gathered before or after official sessions. Over time, “lobbying” ceased to refer only to the physical space and came to describe the organized activity of influencing public decisions.

Lobbyists are strategists representing powerful industries—from pharmaceuticals to arms manufacturers—and seek to steer decisions in their clients’ favor. They operate in capitals like Washington or Brussels, enjoying privileged access to lawmakers, regulators, and media outlets. They fund research that benefits their clients, invest in media campaigns to shape public opinion, pressure legislators with donations or private meetings, and, when evidence threatens them, sow doubt to delay action—a strategy known as “manufacturing uncertainty.”

In the digital age, they’ve adapted these practices, using social media and targeted campaigns that appear organic but are designed to promote products or discredit regulations. The lack of clear definitions of what constitutes lobbying, combined with weak regulations in many countries, allows these industries to exert influence without leaving a clear trail, making it difficult for citizens to understand who funds the decisions affecting their lives.

Health: Profits Over People

Purdue Pharma promoted OxyContin as a safe painkiller despite knowing its addictive potential. The company funded studies and campaigns to downplay risks, contributing to an opioid epidemic that has devastated families. In tobacco, companies like Philip Morris have resisted restrictions on e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products, financing research that questions their risks and lobbying to avoid taxes or advertising limits—especially in countries with weak regulations. These strategies perpetuate public health crises, harming millions, particularly youth targeted by marketing campaigns.

-

The pharmaceutical industry leads U.S. lobbying spending (US$105M in just one quarter of 2025), with tech giants also among the top spenders (each spending >US$10M annually).

Technology: Silencing Dissent

Tech giants like Meta, Google, Amazon, and Microsoft have used lobbying to block privacy regulations, AI oversight, and antitrust laws. Leaked documents from Frances Haugen, a former Meta employee, revealed the company knew Instagram harmed teens’ mental health but prioritized profits over collective well-being. Instead of addressing the issue, Meta invested in strategies to block social media content regulations.

In AI, these companies push for “voluntary” regulations instead of binding laws, arguing strict rules would stifle innovation. This protects their business models but risks mass disinformation and data misuse, while nonprofits struggle to be heard.

Amazon has faced criticism over warehouse labor conditions, where workers report grueling paces and constant surveillance. In 2021, Amazon spent millions to block pro-labor laws like the PRO Act, which would ease unionization. It hired former government officials and ran campaigns to discredit union leaders.

Microsoft leveraged its influence to secure massive government contracts, sidelining smaller competitors. A notable case was the Pentagon’s JEDI contract, where Microsoft defeated Amazon after intense lobbying. Though canceled in 2021 due to legal disputes, Microsoft secured part of a new multi-cloud contract. Such cases show how lobbying concentrates power in a few corporations, stifling competition.

-

When a government entrusts its digital infrastructure to a single giant, everyone’s security and autonomy are at stake.

TikTok: Data and Geopolitics

TikTok, owned by China’s ByteDance, faces scrutiny over data privacy and propaganda risks. The company hired high-profile political advisors and funded media campaigns framing TikTok as a “free speech” platform, downplaying concerns about Chinese surveillance. A 2023 Australian Strategic Policy Institute report found TikTok promoted narratives favorable to China on sensitive issues like Hong Kong and Uyghurs. While teens create viral videos, their data may fuel geopolitical agendas.

-

Tech lobbies manipulate our privacy and ability to make informed decisions.

Climate Denial and Delay

Fossil fuel companies like ExxonMobil knew since the 1970s their products fueled global warming but funded think tanks to cast doubt on climate science, delaying regulations for decades. Recently, they’ve influenced UN treaties like the Global Plastics Agreement, weakening measures to limit plastic production despite ecological harm. These actions worsen storms, droughts, and pollution, ravaging communities.

-

Every time someone claims climate change “isn’t real,” the invisible hand is speaking.

Food: Lies on Our Plates

The Sugar Research Foundation paid scientists to blame saturated fats for heart disease, absolving sugar—a strategy that shaped global dietary guidelines and fueled obesity and diabetes epidemics. Agrochemical firms like Bayer and Syngenta have fought bans on neonicotinoids, pesticides linked to bee declines (essential for pollinating a third of our food). While some countries restrict these chemicals, others still use them, threatening food security.

Finance: Rigging the System

Private equity firms have blocked tax hikes on carried interest, preserving loopholes for the wealthy and starving public services like healthcare and education. In trade deals, tech and pharma lobbies have pushed clauses extending patents and weakening labor/environmental standards, limiting access to generic drugs in developing nations.

The defense industry also wields influence, shaping military budgets and arms deals that prioritize lucrative contracts over social needs. This militarization, driven by ex-officials and trade groups, destabilizes global security.

-

These aren’t just isolated cases—they’re human lives. Lobbyists don’t just shape policy; they transform our health, environment, and trust in institutions.

Resisting the Invisible Hand

Lobbyists thrive on our passivity, knowing modern life leaves little time to question. They frame corporate interests as societal benefits, like claiming environmental regulations hurt the economy—despite evidence that climate inaction costs far more.

But we’re not powerless. We can:

-

Demand transparency in research and campaign funding.

-

Support independent media investigating these dynamics.

-

Verify sources and engage politically.

Initiatives like “lobbying for good,” led by NGOs and activists, show how lobbying can be democratized to advocate for climate justice or labor rights. Tools like AsktheEU or WhatDoTheyKnow let citizens demand lobbyist disclosures, countering their influence.

A Personal Reflection on Censorship

After facing censorship on Meta’s platforms for sharing these investigations on an account dedicated to critical thinking, I was silenced—not for hate speech or lies, but for the (perhaps utopian) ideal of bringing knowledge to spaces ruled by viral idiocy.

I knew, as anyone paying attention does, that social media censors, restricts, and protects its own interests above all. But knowing it and feeling it firsthand are different. Reach becomes a privilege for the docile; uncomfortable truths become crimes. Those who dare question must whisper, careful not to wake the bots patrolling with a severity never applied to disinformation, sexualized content, or hate speech.

This is my despair: living in a virtual public sphere regulated by technocrats who, with totalitarian precision, decide what may exist and what must be erased.

We Are All Consumers

We have built an addicted civilization that selectively criminalizes its own addictions. We have created a world where taking drugs is a way to endure everyday life.

Maybe you have never injected yourself or hidden in a corner to smoke something illegal. But maybe you can’t start the day without coffee. Maybe you have a drink to calm anxiety, an anxiolytic to sleep, or a pill to keep going even when your body says stop.

We are not only talking about substances sold in alleys. There are also those bought with prescriptions, those shared at parties, those drunk at business dinners or family gatherings.

When talking about drugs, it is usually condemned from the pulpit with the label “deviant or addict,” or the consumer is idealized as if they were an enlightened transgressor, but both narratives are wrong.

It is not just a personal choice; it is a system that creates the conditions for these substances to be needed, to circulate, and to be punished or applauded depending on who consumes them.

No one is entirely outside.

We all consume something.

Some do it to perform better, others to forget, others because they don’t know how to carry the weight of the day without external help. Some do it alone, others with friends, many in silence.

The image we have of the “addict” has served to keep us comfortable, as if the problem were out there, in other bodies, in other lives. But drug use is not an individual deviation; it is a mirror of the world we have built.

A History of Power

The history of each substance carries a history of power. Opium did not become a problem when the Chinese smoked it in their traditional ceremonies, but when the British Empire decided to use it to break the Qing dynasty’s economy. The Opium Wars were not wars against drugs but imperial wars for the right to drug entire populations for commercial purposes.

Coca was not born as cocaine. For millennia, Quechua and Aymara peoples chewed coca leaves to endure the altitude, cold, and exhausting workdays. It was traditional medicine, a ritual element. The transformation into cocaine came with the arrival of German chemists in the late 19th century, who applied industrial processes to ancestral knowledge to create a product that could be sold on the streets of Paris and New York.

Tobacco followed a similar path: from a sacred plant used by Indigenous American peoples in ceremonies communicating with the ancestors, it became a plantation commodity grown with enslaved labor, eventually becoming the mass-consumed product that killed more than 100 million people in the 20th century. Every substance we now consider a “drug” has behind it a history of dispossession, extraction, and colonial transformation.

The Same Drug, Different Destinies

In Portland, Oregon, fentanyl has turned entire parts of the city into urban refugee camps. People sleep on sidewalks surrounded by syringes and waste, while businesses close and social services collapse. The official response oscillates between paternalistic compassion and repressive cleaning, never addressing the causes: the housing crisis, job insecurity, the collapse of mental health systems.

In the Appalachians, entire communities have been devastated by the opioid crisis. Here the narrative is different: “working-class families” are victims of “unscrupulous pharmaceutical corporations.” The same politicians who promote a tough stance against crack in urban black neighborhoods advocate for “treatment and compassion” when it comes to opioids in rural white communities.

In Latino neighborhoods in Los Angeles or African American ghettos in Detroit, the same substance is treated as a criminal threat justifying militarized patrols, mass arrests, and disproportionate sentences. The U.S. prison system, the largest in the world, is primarily fed by drug-related crimes committed by black and Latino people.

The cocaine consumed in Wall Street bathrooms is chemically identical to that sold on Bronx corners. The difference is that one finances corporate bonds, the other justifies urban warfare.

In Germany, nitrous oxide is freely sold in supermarkets. Young people inhale it in parks and festivals without significant police scandal. Its recreational use is tolerated because it comes from white middle-class sectors and does not threaten any established order. If the same substance were consumed by Turkish immigrants or Syrian refugees, the response would be radically different.

Latin America

Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia live a war they did not choose. Their territories have been turned into battlegrounds of a chemical war that benefits everyone except them. Farmers cultivate coca because it is the only way to survive in rural economies devastated for decades. Young people are recruited into drug trafficking because they feel they have no other opportunities.

In Miami, New York, Madrid, London, production is criminalized but not consumption. It’s easier to bomb labs in the Colombian jungle than to arrest bankers laundering money in tax havens.

The “war on drugs” in Latin America has caused over 300,000 deaths in Mexico, displaced millions of farmers, militarized entire territories, and turned the State into a minor partner of organized crime—all so drugs continue flowing as easily to consumer countries.

The cocaine that arrives in Europe does not decrease in price, purity, or accessibility. The war works for everyone except those who claim to benefit.

Drug use in the “First World” flourishes because material progress has not brought psychological well-being; on the contrary, it has multiplied substances that compensate for its lacks.

The Pharmacy of Survival

The nurse who depends on three substances to endure her shift, the programmer who uses microdoses of psychedelics to boost creativity, the retired woman who needs daily medication to cope with loneliness: none appear in addiction reports.

The economic system requires bodies available 24/7, minds optimized for productivity, emotions regulated for consumption. Legal and illegal drugs make this impossible demand possible.

Antidepressant use has tripled in the last two decades in OECD countries. Non-prescription stimulant use has increased 350% among U.S. college students. Anxiolytic use among working women has grown exponentially. These are not health epidemics but chemical adaptations to inhuman living conditions. The legal pharmaceutical market and illegal drug trafficking are two expressions of the industrial commodification of distress. Both produce dependency, generate extraordinary profits, and require vulnerable populations to sustain growth. The difference is profit margins and distribution mechanisms.

The Double Standard of Regulation

Why does alcohol, which kills 3 million people a year according to WHO, sell on every corner, while psilocybin, showing promising results against treatment-resistant depression, remains illegal in most countries?

Why does tobacco, with no recognized medical benefit and the leading cause of preventable death worldwide, trade freely, while cannabis, used medicinally for millennia, still sparks controversy?

The answer is not pharmacology but politics.

Legal substances generate profits for established corporations, are consumed by politically powerful sectors, do not threaten productive functioning, and come from hegemonic cultural traditions.

Illegal substances are associated with racialized minorities, come from non-Western traditions, are used by marginalized sectors, and may generate experiences questioning the established order.

This classification is not based on impartial scientific criteria but political decisions determining who can alter consciousness and for what purpose. It defines which mental states are acceptable within the established order and which must be repressed, medicalized, or punished.

Addiction as a Social Diagnosis

A teenager using drugs is not an individual case of “neurological dysfunction.” It is a social symptom of a world offering no dignified alternatives to millions of young people. Their use emerges not in a vacuum but in contexts of state abandonment, structural violence, lack of opportunities, and community breakdown.

Problematic drug use appears in impoverished territories, racialized populations, sectors excluded from education, work, and health services. It is not coincidence but structural causality.

Drugs occupy spaces that should be filled by education, decent work, culture, sports, community. Criminalizing users is like arresting thermometers for showing a fever.

Community as the Antidote

People consume more when isolated, lacking meaningful connections, or lacking purpose in daily existence. The highest addiction rates correspond to the most individualized, fragmented societies.

This implies:

-

Jobs respecting biological rhythms instead of demanding total availability.

-

Cities designed for human encounters, not just for goods circulation.

-

Health systems addressing social causes, not just individual symptoms.

-

Education developing critical thinking, not just job skills.

-

Economies prioritizing collective well-being over private accumulation.

The question is not how to eliminate drugs but how to create life conditions that do not require constant chemical alteration of consciousness to be livable.

What is missing is not knowledge but political will to question interests benefiting from the status quo.

What you resist, persists.

Why, despite decades of analysis on the consequences of rampant consumerism and the commodification of life, do we still fail to see any genuine transformations? What makes such a widely criticized system not only remain intact but become even stronger?

Perhaps the biggest mistake the system’s critics have made is giving it a name that allows for its defense. “Capitalism” immediately evokes its opposite: “socialism” or “communism.” This binary polarization allows the system to take refuge in the false idea that it represents freedom versus totalitarianism, democracy versus dictatorship, prosperity versus poverty. By naming it, we have turned it into an ideological choice.

What we are facing is not an economic system that can be reformed or replaced by another; it is a way of existing that defines how we think, desire, coexist, and treat the world. It turns people into tools, nature into raw material, and time into a resource.

Its analyses range from the bureaucratization that chains freedom, the surveillance that normalizes obedience, the consumerism that stifles critical thought, to media manipulation, the spectacle that replaces reality, the crises that enrich a few, the culture that standardizes, the ideology that justifies exploitation, the empty jobs that alienate, and the technology that turns us into data. These ideas, celebrated and debated, have not been enough to break the system. On the contrary, it seems the system easily absorbs criticism as if it were part of its design.

This transformation operates at such a deeply ingrained level that even its most ardent critics end up replicating its dynamics. Dissident movements organize themselves like businesses, compete for audiences, and commodify their message of resistance. Universities that study inequality function like corporations that exploit precarious academic labor. Environmental activists travel by plane to denounce carbon emissions. Criticism has become just another product in the marketplace of ideas, and its producers, other entrepreneurs of outrage.

The Cycle of Surveillance and Performance

Both in systems that call themselves free-market and in those that proclaim themselves socialist, they agree on subordinating life to a machinery that processes human beings as raw material. In 20th-century state socialism, people became resources for the party, for the revolution, for the five-year plan. In neoliberalism, they become resources for the market, for growth, for competitiveness.

Central planning and the free market share the same project: the efficient management of populations.

The Transformation of Domination

What we face is not classic domination where a clearly identifiable bourgeois class exploited an equally defined working class. Domination is now more diffuse and, therefore, more total. There isn’t a group of villains conspiring; there are millions of people, including the system’s critics, unconsciously reproducing its patterns.

Power is no longer exercised through repression. It doesn’t force us to work; it convinces us that we are entrepreneurs. It doesn’t forbid us from protesting; it turns protest into viral content. It doesn’t censor criticism; it monetizes it. This form of domination is more effective than any dictatorship because it acts from within, shaping desires, ambitions, and ways of understanding success.

There is no master plan; there are millions of individual choices that move toward the same destination, shaped by a common pattern that guides what we believe we are freely choosing. We are free to choose between jobs that wear us down and allow us to pay for services that the community once provided. We are free to choose between products we don’t need and lives that don’t feel like our own. This freedom is a form of domination that feels like emancipation, an oppression that is experienced as a choice.

The prisoner who decorates his cell feels free; the consumer who chooses from thirty brands of cereal experiences diversity; the worker who manages their flexible time believes they are in control of their life. The cage has become so comfortable and beautiful that its inhabitants defend it against those who point out the bars.

24/7

The system operates twenty-four hours a day. Financial markets never sleep, social media never shuts down, notifications never stop. Life is no longer synchronized with circadian rhythms, and even sleep becomes an object of optimization: apps that monitor sleep patterns, supplements to sleep better, techniques to be more productive while we sleep.

All of this leads to anxiety that the very system offers to cure. Meditation apps for stressed workers, wellness retreats for exhausted executives, life coaches for people who have lost their sense of purpose.

In 2023, 40% of workers felt their jobs were meaningless, trapped in a routine of alienation. The pressure to perform is exhausting: 55% of workers in developed countries reported burnout in 2023. Even spirituality becomes a technique to be more productive, with mindfulness retreats costing up to $10,000 per week.

The Desire Factory

The system manufactures desires, continuously generating new forms of need, aspirations, and discomforts that can only be alleviated through consumption. It commercializes identities more than objects, emotional bonds, and forms of belonging.

Global advertising spending amounts to millions of dollars convincing us that we are incomplete without the next product.

The loneliness epidemic that is sweeping the world is not a personal psychological problem but a product that fuels compensatory consumption. We buy to fill voids, we work to escape isolation, we connect digitally to avoid facing real disconnection. And in the meantime, the system offers us more products, more platforms, more ways to monetize our loneliness.

Every purchase promises to fill a void that the system itself creates, but satisfaction is fleeting, designed to feed the next need. If an object truly filled our deficiencies, the economic machine would lose its momentum. That is why obsolescence is not limited to the material plane.

Each acquisition must pave the way for the next, each relief must become a prelude to a new frustration, each success a reminder of what is still missing.

The existential crisis that manifests as anxiety, depression, and addictions is the consequence of a system that cannot provide meaning because its logic is absurd: to accumulate for accumulation’s sake, to grow for growth’s sake, to consume for consumption’s sake.

The Plundering of the Earth

Each year we extract about one hundred billion tons of materials from the Earth: minerals, fossil fuels, biomass. The oceans lose ninety million tons of fish annually, far exceeding their capacity for regeneration. A third of the world’s agricultural soils are degraded by industrial agriculture. The Amazon, which took millions of years to form, has lost almost a fifth of its area in five decades.

This exploitation does not respond to our needs but to the system’s need to grow infinitely. Most of the resources extracted are turned into disposable objects that last months or years: clothes that are worn a few times, electronics that become obsolete, packaging that is thrown away immediately.

Each smartphone contains more than sixty elements from the periodic table, extracted through mining that devastates entire ecosystems, for devices that are replaced every two years.

Greenhouse gas emissions continue to grow because the system needs to burn more energy, produce more objects, and transport more goods. The proposed solutions (renewable energy, electric cars) keep the premise of infinite growth intact; they only change the energy sources to feed the same voracity.

Normalized Violence

There is enough food for 12 billion people, but hunger persists. There are empty houses, but millions are homeless. There are medicines that could save lives, but they are inaccessible because they are not profitable. This violence is not perceived as such because it is presented as the natural result of “scarcity” or “competition.” But there is nothing natural in a system that produces abundance and scarcity at the same time. This demonstrates the ultimate truth of the system: it does not exist to satisfy our needs, but to valorize capital.

Needs are only met if they are profitable; otherwise, they are ignored, no matter how much suffering they cause.

The system subordinates collective decisions to market imperatives. Political freedom exists in theory, but in practice, it is limited by the freedom of capital to move, destroy, and accumulate without restrictions.

Revolution Inc.

Dissent becomes a commodity. T-shirts with a revolutionary’s face are sold in shopping malls, manifestos against consumerism go viral on platforms funded by advertising, and denunciations of the climate crisis become green marketing campaigns.

The system does not repress its critics; it absorbs them and turns them into content.

Outrage against inequality is transformed into bestsellers sold in the same bookstores that promote guides to becoming a millionaire. Sustainability becomes a market niche, with reusable bottles and apps to measure your carbon footprint, while the corporations that are devastating the planet sponsor climate summits. This capacity for co-optation not only neutralizes criticism; it turns it into proof of the system’s freedom.

Those who question the system are often validated by the number of followers, measurable impact, and media presence. Corporate language infiltrates even the most genuine attempts at transformation.

Charismatic leaders become CEOs of discontent. The left and the right compete in the same political market, differentiating themselves only in their value propositions for different segments of promise consumers.

Liquid Meanings

Terms like “freedom,” “democracy,” “progress,” or “innovation” have lost their concrete meaning and can be used to defend almost anything. Freedom is invoked both to eliminate financial regulations and to justify digital surveillance. Democracy serves both to talk about citizen participation and to conceal the manipulation of opinions through algorithms.

The system presents itself as a defender of all values while acting against them. It can call itself democratic while concentrating power in private corporations; it can talk about freedom while reinforcing forms of control that do not require visible repression.

The effect is a confusing landscape, where it is no longer possible to distinguish between real criticism and propaganda. Both those who support and those who question the current state of affairs use the same words: freedom, justice, well-being, sustainability. This ambiguity prevents clear thinking and makes it difficult to propose alternatives without them sounding like simple tweaks to what is already established.

The Pseudo-Alternatives

The system has the ability to create false alternatives that channel discontent without endangering its structure. Initiatives such as green capitalism, the circular economy, social entrepreneurship, or technology “with a human face” seem like transformative proposals, but deep down they reinforce the very model they claim to question.

“Green capitalism” generated $1.5 trillion in 2024, but resource extraction did not decrease (Bloomberg, 2024). Agribusiness, which controls 60% of agricultural land, sells genetically modified seeds as sustainability while destroying biodiversity (FAO, 2023). The “collaborative economy” concentrates wealth: 80% of the profits from platforms like Uber go to 20% of its executives (Oxfam, 2024). These solutions give the illusion of change but reinforce the same structure.

These ideas function as escape valves, allowing the system to absorb criticism without modifying its operations. A feeling is generated that something is changing, when in reality everything continues to function as before. The system adapts, it renews its appearance, but it keeps its fundamental operations intact. It is a reformism that goes in circles: it promises transformations, but only delivers updated versions of the same problem.

The most difficult thing to detect is that these proposals are not entirely false. They often have some truth to them and point to real needs. But that small core of truth is subordinated to the same model it is trying to soften. Instead of attacking it, they end up reinforcing it from within, as part of a formula that always changes to stay the same.

The Administration of Life

What defines the system is not only economic exploitation but also the complete management of daily life. Almost every aspect of our existence is organized, monitored, or guided by some kind of mechanism. Health is managed with private insurance and wellness apps. Education is measured by rankings, grades, and performance metrics.

This type of control does not act repressively, like authoritarian regimes; it is persuasive and productive. It does not directly prevent us from doing something but guides us toward what is considered “useful,” “efficient,” or “profitable.” It does not eliminate creativity, but it channels it into formats that generate profit. It does not prohibit communities, but it turns them into networks of users or consumers.

Transcending Categories

Perhaps it is time to abandon the vocabulary that traps us in false oppositions. It is not about defending or attacking ideological labels but about recognizing that we inhabit a form of reality organization that transcends traditional political categories. It is not a system that can be reformed or overthrown; it is a transformation of consciousness that must be changed from within.

The cracks already exist: in acts of care that cannot be quantified, in relationships that resist being mediated, in moments of contemplation that escape productivity, in forms of knowledge that do not seek immediate application, in communities that prioritize collective well-being over individual accumulation, in movements that protect territories without turning them into resources.

It is necessary to create ways of living that do not need to be validated by numbers, that do not turn everything into a resource, that do not live under the constant pressure to justify their utility. Ways of life that may not even need a name, because it will be enough for them to be habitable.

When Everyone Teaches, Who Learns?

An analysis of how intellectual authority is built on the internet and what happens when knowledge becomes viral content.

“The teacher who has never been a disciple is an impostor. He who does not know he is still a disciple is a danger.”

Never before have so many aspired to teach while having so little to offer. Never before has the position of the teacher been so easy to occupy and so difficult to legitimize.

This new form of intellectual authority is the construction of subjectivities that need to teach in order to affirm themselves—subjectivities that turn pedagogy into an extension of the ego and knowledge into a performance. In this environment, there emerge those who adopt the role of guide or reference without the necessary training, institutional backing, or ethical commitment.

In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche proclaimed the death of God and, with it, the death of all transcendent authorities. What he did not foresee was that this death would not lead to the Übermensch, but to the proliferation of petty gods, each with their own revelation.

The pseudo-teacher is the bastard child of democratization. They are born when access to communication tools becomes universal, but the necessary training to use those tools with intellectual responsibility does not. Their equation: technology + ego + audience = authority.

Their origin is tied to three major historical shifts that have redefined today’s intellectual landscape.

The first is the crisis of educational institutions. Universities, once temples of knowledge, have become degree factories. Education has been commodified, bureaucratized, and stripped of substance. In this scenario, the pseudo-teacher’s anti-institutional critique thrives, building influence by discrediting traditional figures of authority.

If traditional authorities are illegitimate, then any alternative voice gains legitimacy by opposition. The pseudo-teacher does not need to prove their credentials—they only need to discredit the credentials of others. It is a zero-sum game where authority is obtained by destroying other authorities.

If anyone can be a teacher, there is no need to be an apprentice; if all knowledge holds equal value, then criteria for evaluation disappear; if every opinion deserves equal respect, then specialization becomes meaningless. Thus, we move from open knowledge to widespread confusion.

The second transformation is the temporal acceleration that Byung-Chul Han describes as destructive of contemplation and depth. The pseudo-teacher is both a product and a producer of this acceleration. Their pedagogy is based on the immediate delivery of consumable content, on the instant gratification of the desire for knowledge.

The time available for learning has drastically shrunk: university courses that once took years are compressed into intensive seminars, books are summarized into infographics, complex theories are explained in ten-minute videos. This temporal compression inevitably leads to superficiality, as certain cognitive processes require time to settle.

The third transformation is the fragmentation of knowledge brought about by digitalization. Knowledge is no longer presented as a continuous process or an interconnected system, but as a series of fragments designed for immediate consumption. A short video on quantum physics can have as much visibility as a university course; a social media thread on philosophy can reach further than a carefully crafted academic work. In this context, the idea that understanding something complex requires prior steps, time, and gradual training is lost.

Pseudo-teachers present fragments of knowledge as complete wholes, stripping concepts from their theoretical contexts, disconnecting ideas from their traditions, and offering superficial syntheses as deep analyses.

On digital platforms, everything appears to hold equal value: a serious analysis and an improvised opinion circulate in identical formats, compete for the same attention, and are measured by the same metrics.

The Devaluation of Knowledge

Empty authority generates an inflation of knowledge similar to monetary inflation: the amount of content presented as “knowledge” multiplies, but its quality is devalued. This inflation has consequences, including disorientation—where the audience is overwhelmed by the sheer volume of available “knowledge” and loses the ability to distinguish between valid and simulated information.

It also leads to the devaluation of intellectual effort: Why study for years when you can get “the truth” in a ten-minute video? Empty authority devalues effort and promotes a culture of instant knowledge.

A piece of content is “truer” if it has more likes, more valid if it generates more reactions. Criteria of validity are replaced by criteria of popularity.

Pedagogical Imposture

Different forms of “authority” have emerged from the dynamics of digital platforms. Each adopts various ways of constructing authority, but all attract large audiences without requiring serious commitment to learning.

-

The Critic of Modern Society: This figure builds authority through generic critiques of “modern society,” “the system,” or “the matrix,” without providing in-depth analysis or concrete proposals. Their pedagogy consists of pointing out social issues (consumerism, alienation, media manipulation) as if they were the first to discover them.

-

The Consciousness Awakener: This archetype positions itself as responsible for “awakening” the sleeping masses. They use apocalyptic rhetoric blending conspiracy theories, superficial social critique, and promises of revelation. Their authority relies on supposedly possessing hidden knowledge that “they” don’t want us to know. They divide the world into “the asleep” and “the awakened,” appealing to paranoia and the desire to belong to an exclusive group of “enlightened” individuals.

-

The Self-Help Guru: This guru mixes elements of psychology, oversimplified Eastern philosophy, and self-help techniques. Their authority is built on the promise of quick personal transformation, using their own “evolution” as proof. They reduce ancient spiritual traditions to self-help formulas, trivialize deep psychological and philosophical concepts, and present their biography as evidence of their methods’ effectiveness.

-

The Self-Taught Intellectual: They present their lack of formal education as a virtue, claiming that academia “limits” thought. They indiscriminately mix elements from different philosophical, scientific, and cultural traditions without truly understanding them. Their narrative is elaborate enough to seem rigorous but accessible enough that no specialized knowledge is needed. They offer superior knowledge without effort.

-

The Armchair Political Analyst: Lacking training in political science, history, economics, or sociology, they confidently interpret political dynamics. Their arguments rely on clichés, unacknowledged ideological biases, and hasty generalizations. Their authority rests on the apparent ability to “make sense” of what others supposedly fail to understand.

-

The Amateur Science Communicator: Their authority is built on making technical concepts “accessible.” Though lacking scientific training, they present theories as absolute truths. They borrow science’s prestige but strip concepts of their uncertainty and methodological context. Their “popularization” often creates more confusion than knowledge.

The End of Intellectual Traditions?

Empty authority contributes to the erosion of intellectual traditions—understood as the transmission of knowledge across generations. Instead of traditions, we have trends; instead of schools, we have influencers; instead of teachers and disciples, we have content producers and consumers.

Without solid traditions, intellectual memory is lost. Each generation must reinvent the wheel, rediscover long-known truths, and repeat past mistakes. The pseudo-teacher, unaware of their discipline’s history, presents centuries-old ideas as revolutionary breakthroughs.

Intellectual Humility

Whoever aspires to teach must first recognize how much they do not know. —A Socratic principle.

The true teacher never stops being a student. They remain open, curious, willing to revise their ideas, admit mistakes, and consider other viewpoints. Intellectual humility is not just an attitude but a constant practice: those who cultivate it avoid imposing rigid answers, reducing problems to easy formulas, or confining reality to comfortable explanations.

Everyone reading this can identify, in their daily lives, ways in which intellectual authority is constructed. Detecting these patterns does not require great effort—only critical attention in the spaces where knowledge circulates.

The quality of knowledge depends not only on who produces it but also on how we receive it. In this constant exchange, what we value as knowledge is defined.

HOW. THEN I THINK

The loss of critical thinking is often attributed almost entirely to digital technologies. Screens, algorithms, and social media are singled out as the main culprits behind attention fragmentation and the deterioration of our mental capacities. While this perspective is partly correct, it overlooks another crucial factor.

We think with our bodies, with our history, with what we inherit and what we suffer. There is no isolated “thinking self” suspended in some metaphysical ether. There are elements and circumstances that shape our cognitive abilities. Among these determinants, one stands out for its daily and persistent influence: food. Every bite sends chemical signals to the body that affect the mental processes through which we perceive, decide, and reason.

It’s not just algorithms that shape our decisions—what we eat does too. While attention focuses on the effects of digital exposure, the biochemical burden damaging our cognitive functions from within goes unnoticed.

The Information You Eat

Every food is a chemical message that our body reads and translates into physiological states. When we consume sugar, we trigger hormonal cascades that have evolved over millions of years to respond to survival situations. The body interprets a glycemic spike as a signal of sudden abundance followed by imminent scarcity, responding with patterns of desperate accumulation and anticipatory anxiety.

Blood sugar spikes create hormonal roller coasters: energy surges followed by crashes, euphoria followed by depression, hyperactivity followed by lethargy. It’s impossible to think clearly when the body is on this biochemical ride.

When we eat ultra-processed fats, we give the body defective building materials. Cell membranes stiffen, intercellular communication falters, neurotransmitters struggle to move fluidly. The brain begins to function like an engine with dirty oil—slow, clogged, prone to failure.